UPDATED Fetching GitHub Pull Requests With Git

GitHub’s merging of pull requests has had some healthy criticism over the time. An example can be found here and here (from the man himself)

Usually the people making these claims have specific requirements for their workflow. Understandably, GitHub can’t support everybody’s way of doing things. GitHub is not fully compatible with Linus’ workflow, but it’s actually possible, with some work on behalf of both submitter and maintainer, to have some flexibility in how they make and merge(rebase) pull requests.

There is some criticism that GitHub should accept here and that’s poor advertising of how Pull Requests work. The following things I’ve discovered by trial and error, and are really cool features that deserve more emphasis on behalf of GitHub (perhaps in a shape of a What happens to a pull request when I … FAQ). So, without further ado,

What happens to a GitHub Pull Request when I…

…use the recommended commit message format?

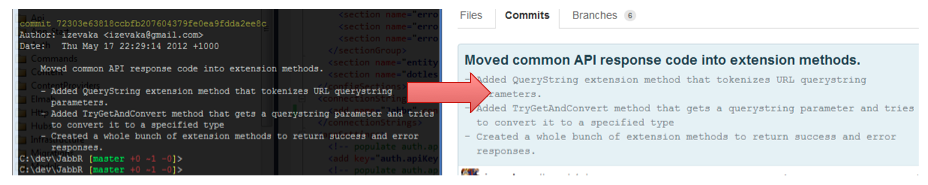

When you use the 50 character one-line, followed by detailed description with hard line breaks at ~70 character mark AND that commit is at the tip of the branch at the time of making PR, magic happens. The Pull Request title and description come from one-line and detailed description respectively:

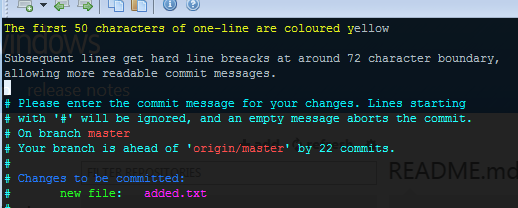

To read more about recommended commit format check out Commit Guidelines in the Git Book. Also did you know that by default, vi, the editor configured for git, will help you with creating kosher commit messages when you simply type git commit?

###…push more commits to a branch that I’ve submitted a Pull Request from? To be fair, PR doco does say that the commits are added to the request, which is cool. How does GitHub decide whether or not the PR tracks new commits made in your fork? My assumption is that branches are tracked, whereas tags and commit SHA1s aren’t.

###…make a Pull Request Based on a Tag/Commit? Pull Request UI looks like this, and to tell the truth, I find a single line that says “Head branch · tag · commit” a little confusing. “Head branch” that PR tracks whatever is in that branch. “Tag” and “Commit” just means a single commit.

###…rebase and force push to the branch that has an outstanding Pull Request? This one I haven’t tried, but have on good authority that what happens is exactly what you want to happen - i.e. the Pull Request contain commits that are different between the two branches. Example (lets assume commits B and C were made after the pull request was made):

Mainline : A - B - C

\

Your fork: D - E

#What PR looks like at this point

#Commits:

- D

- E

You have a conversation with the maintainer and they ask you to clean up the PR and make it look like it’s based off the HEAD of mainline and squash them. You Rebase off mainline and force push the following:

Mainline : A - B - C

\

Your fork: F (squashed D and E)

#What PR looks like at this point

#Commits:

- F

Brilliant! I actually support controlled use of rebase and force push and this seems like a good use for it. Commits in topic branches that are subject to pull request approval are up for grabs and no one should be relying on them anyway. It also means that it’s possible for submitter to rebase to account for new code being added to the mainline, not the maintainer. Once the commits are merged into mainline, the submitter can pull and the result would just be a fast forward.

##Merging Pull Requests This is where GitHub gets insanely cool and actually is the reason why I started writing this post in the first place. I don’t really like not being able to rebase pull requests into mainline. Some people care a lot about it, some people don’t, but having a clear unpolluted mainline branch is essential, especially since you only have one canonical branch. I really don’t like the “Merge Pull request #492” as a merge commit, even if there were no conflicts.

GitHub Pull Request doco says that in order to perform the merge manually, the maintainer must add the submitter’s fork as a remote and then merge/rebase/whatever in their local repository before pushing to the mainline. As a maintainer I would hate to have to do that. Luckily there is a way to do that much easier and is described in this post.

Just so you understand the gravity of what’s going on here, this means you can fetch a pull request by number without creating a remote!

git fetch upstream pull/123/head:pr_123

After running the above command you would have a local branch that corresponds to the contents of that pull request. Let’s see if we can make it more usable without creating a shell script (which may not work on Windows).

Disclaimer : Since I can’t find any information about this GitHub specific refspec apart from the quoted blog post, I have no idea if this is some sort of an “unpublished API” or a side effect of how GitHub does things internally. All I can say is at the time of writing it works on my machine :)

Update : Paul Betts explains on twitter why GitHub stores pull requests in the source repository and it is because the submitter might delete their fork straight after creating a PR.

Fetch all Pull Requests (even closed ones)

Just execute the following commands and you’ll be able to fetch all pull requests by simply executing git fetch pr. Pull requests will be stored in a remote as individual remote branches. So a pull request 123 will be accessible as ‘pr/123’:

git remote add pr https://github.com/upstream/repo.git

git config --local --unset remote.pr.fetch

git config --local --add remote.pr.fetch "+refs/pull/*/head:refs/remotes/pr/*"

Fetch individual pull requests (by number)

We can use shell git alias (i.e. a git alias that can execute any shell command) to fetch individual pull requests and put them under a remote pr. You don’t have to follow above steps to create a pr remote:

git config --global alias.fetch-pr '"!f() { git fetch $1 refs/pull/$2/head:refs/remotes/pr/$2; }; f"'

Just to explain what’s going on there:

!means a shell aliasf()defines a shell function called “f”{ git fetch $1 refs/pull/$2/head:refs/remotes/pr/$2; }is the body of the function. It fetched from the remote (first parameter) a specified pull request (second parameter) and places it as though it came from a remotepr.finvokes the function.

You can run this as follows:

git fetch-pr origin 123

#After running the command you'll be able to see the history

git log pr/123

Rebase individual pull requests into current branch

This is an alias that would fetch the PR and rebase it into the current branch, so that the PR commits look like they have been applied to the HEAD of the current branch:

git config --global alias.rebase-pr '"!f() { git checkout -b pr_$1 pr/$1; git rebase @{-1}; git checkout @{-2}; git rebase @{-1}; }; f"'

Usage is like so:

git rebase-pr 123

Note that in order to run rebase-pr, you would have needed to run ‘fetch-pr’. rebase-pr is not very conflict friendly (not that conflicts coming from submitters are acceptable). If you do have a conflict and hit git rebase --continue, you end up on a temporary branch pr_NNN. You will then need to switch back to master and rebase pr_NNN. So the sequence of steps would be:

git rebase --continue

git checkout master

git rebase pr_NNN

git branch -D pr_NNN

With these things available in your git toolbox, you should hopefully be able to reduce the friction of the Fork + Pull Model workflow even further.

Happy coding!

blog comments powered by Disqus